I have a confession to make. I am the child of immigrants, one of whom crossed our southern border a century ago, and so I am extremely sympathetic to the many people arriving at our southern border in search of a better life.

The demonizing of migrants for political ends by Donald Trump and other political figures angers me. The demonization needs to stop. This dehumanizing strategy is all about creating fear of others in an effort to manipulate people to support him as he promises to protect them from the demonized. It is a classic political manipulation technique. As a journalist, I witnessed how such demonization unfolded in the Rwandan genocide, and I wrote a book on Al Qaeda in eastern Africa, in which I recounted how Osama bin Laden and his subordinates used demonizing techniques to make people fearful, positioning them to commit violence against the “others.” We, Americans, can do better than this.

And, as I write this article, Mr. Trump advocates the deportation of millions of undocumented residents if he were to assume the presidency in 2025. This would amount to one of the world’s largest ethnic cleansing operations since World War II, as, given Mr. Trump’s past performance, deportations would likely affect dark-skinned people and Muslim people the most. Deportations on this scale would even surpass the two campaigns of mass deportations of Americans of Mexican descent and Mexican residents that took place during the administration of Herbert Hoover and again under President Dwight Eisenhower.

My mother was born in Mexico, and when she was two and a half years in July 1923, Mom crossed the border into the United States with her mother – my Abuelita (grandma in Spanish) – and three brothers. They were leaving a country that had been plagued by revolutionary violence. Indeed, the famous Mexican revolutionary militia leader, Pancho Villa, was assassinated the same month that Abuelita crossed the border with her children to enter the United States. So, their situation was not unlike many of today’s migrants fleeing political and gang violence for metaphorical safe harbors in the United States.

Abuelita’s crossing of the border at El Paso also occurred thirteen months before a new bigoted U.S. immigration law went into effect. I say bigoted because it explicitly favored immigration from northern and Western Europe. In the words of one of the strongest Senate backers of this bill, “The racial composition of America at the present time thus is made permanent.” The legislation succeeded in reducing immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, from regions with darker-skinned peoples, and it explicitly prohibited immigration from Asia. The New York Times captured the spirit of this legislation with the headline: “AMERICA OF THE MELTING POT COMES TO END.” This bigoted legislation was reversed in 1965 with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s signing of the Immigration and Nationality Act on Liberty Island in New York Harbor.

When Abuelita came with her children, there was no visa requirement. All that Abuelita had to do was to pay a $8 head tax to the El Paso Electric Railway company that monitored border crossings for the Federal Immigration Service. There was no Border Patrol when they crossed; it too was established with the 1924 immigration law.

I have a copy of Abuelita’s passport photo when she came into the United States. Abuelita is surrounded by her four children. My Mom looks so adorable in the photo.

So, you might appreciate how outraged I became when our government forcibly separated more than 5,000 children from their parents between 2017 and 2018 after then President Trump authorized the “Zero Tolerance” policy at our southern border. Babies and toddlers were literally ripped from their parents’ arms under this horrific practice. Thousands of families were torn apart. I imagined the trauma and horror that Abuelita and her children would have experienced had they been forcibly separated.

So, you might appreciate how outraged I became when our government forcibly separated more than 5,000 children from their parents between 2017 and 2018 after then President Trump authorized the “Zero Tolerance” policy at our southern border. Babies and toddlers were literally ripped from their parents’ arms under this horrific practice. Thousands of families were torn apart. I imagined the trauma and horror that Abuelita and her children would have experienced had they been forcibly separated.

My outrage motivated me to join thousands of others near the White House to protest the family separation policy. Probably not since the mass internment of Japanese Americans during World War II have we as a country engaged in such a large-scale official deliberately cruel activity.

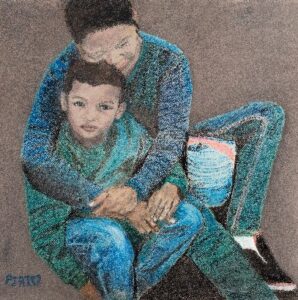

My outrage also motivated me to paint a portrait of a mother and child at the border, which I have entitled Borderless Love. The painting was inspired by a photo I saw of a mother and her children under Border Patrol custody.

My outrage also motivated me to paint a portrait of a mother and child at the border, which I have entitled Borderless Love. The painting was inspired by a photo I saw of a mother and her children under Border Patrol custody.

Following litigation, the Trump-approved family separation practice was halted by the court. At the same time, the government proved unprepared to reunite parents with their children, many of whom had been sent to states throughout the country to stay in shelters or with foster families.

After the American Civil Liberties Union’s lawsuit on behalf of thousands of traumatized children and parents who were forcibly torn from each other, a federal court approved a historic settlement in December 2023. In the words of the ACLU’s lead attorney in this case:

While this settlement alone can’t fix the unfathomable damage done to these children, it does provide hope and support that didn’t exist before. But there remains enormous work ahead to implement this settlement, including reuniting the hundreds of children who are still separated from their loved ones after all these years. . . . No family should be forced to go through this nightmare and tragedy ever again.

Before moving on to the story of Pedro, it may be important to note that my three uncles who crossed over into the United States in 1923 with Abuelita and Mom served in combat in World War II, and another uncle, Ferdie, who was born in the United States, died during the Battle of the Bulge in the European campaign while serving our country’s armed forces. Uncle Ferdie was 20 years old.

I couldn’t help but feel compassion when I met Pedro. when he was installing dry wall at a construction site. The story he told runs so counter to the narrative Mr. Trump and his allies spread about migrants. Mr. Trump calls them rapists and murderers, saying that countries all over the world are emptying people from their prisons and insane asylums, who then cross over the border into our country.

I introduced myself to Pedro and soon we were talking in Spanish. In my broken Spanish, I told him my Mom had been born in Mexico, being aware that this part of my heritage creates a quick rapport with immigrants from Spanish-speaking countries.

And, indeed, Pedro opened up to me. He explained that he had left Guatemala where he had been threatened with violence by gang members. His family came up with $15,000 to pay people who would bring him across the border. This was a huge sum for his family, he said.

His handlers took him to the border in western Texas, where he then had to walk alone along a desert trail without food and water for more than three days. He told me how he came across bodies of people who had not survived the trek. Pedro also told me that he was bitten by a snake while on the trail, but thankfully, it was not venomous.

It is unclear to me how he made it to the Miami area once he made it through the desert. He lived in Miami for four years before making his way to the Washington D.C. area. He said he liked the DC area.

Pedro then became very sad, as he related to me that his father had died in Guatemala four months earlier. He lamented the fact that he had not seen his dad since leaving Guatemala. Pedro added that he did not have family or a girlfriend in the United States and how he felt lonely being by himself. With the death of his father, Pedro is determined to return to Guatemala to help care for his mother who is now living alone, and he would do so despite the dangers of gang violence that he would face there.

I asked him if he would later return to the United States. He said, “no,” explaining that it now costs $20, 000 to be escorted by handlers to cross the border. Besides, he said, “his mother needed his help in Guatemala.” He is committed to her care.

In telling Pedro’s story, I want to promote a more human view of people crossing the border, to remind us all that they experience fear and love like we all do. Demonizing those seeking a better life in our country serves no purpose other than to divide. Certainly, it plays no role in finding solutions to the real challenges posed by the large numbers of people seeking a better life in our land.

I confess not be an expert in immigration law, but I do know that ending the demonization of immigrants is important to finding humane solutions to the many challenges associated with immigration. This includes working with other countries to find solutions to the violence and poverty that oblige people to leave their homelands. For those immigrants who have already made their way here, which has been the promised land for generations of immigrants, it means treating them with dignity and respect as they seek to become productive members of our society. It also means providing support to our communities impacted by large numbers of immigrants to ensure that these communities are able to thrive.